Notes on the State of Software

I get emotional about software at times, and by getting emotional I mean getting upset. I want to dig into the issues frustrating me and what should be done about them.

What’s bad

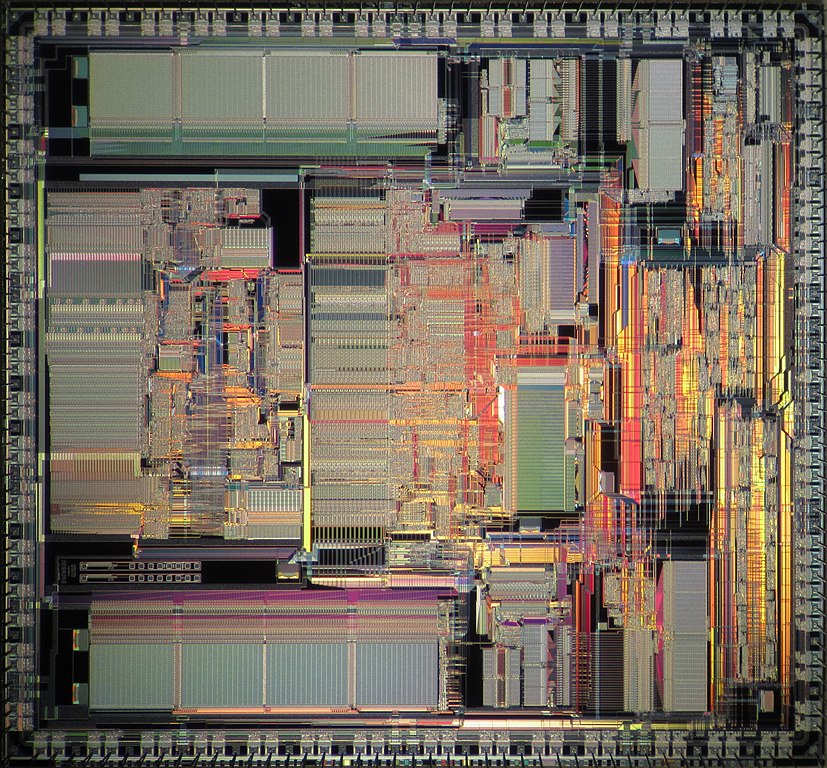

Computers are beautiful and empowering devices, they are the highest technical achievement of humanity. Just look at this die shot to convince yourself:

Die shot by Pauli Rautakorpi, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

Die shot by Pauli Rautakorpi, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

This beauty and power is hidden from most people. The average person today thinks of computers as confusing and awkward sources of frustration. They put up with computers for the useful, entertaining and addictive services computers offer, but dislike the experience of using computers itself.

Control

Ownership and control of software and computers is eroding in front of our eyes, yet few care, as the current state of affairs is comfortable enough. I.e., I often hear people say: “Sure, I don’t own the ebooks I buy on Amazon, but I can read them just fine, so why would I care?”

The artificial limitations imposed by vendors reinforce the widespread belief that computers are inherently restricted and difficult to use. This is a misconception. Take interoperability: our computer systems could work together seamlessly, as the web demonstrates. It could be this way with most if not all systems we use daily.

Vendors employ numerous strategies to limit how we use our computers. Consider how Apple uses iMessage to bully teens into buying iPhones or how Apple has adopted HEIC as their default image format, making it harder to share photos.

Or consider how vendors try to lock down the devices they sell, so only their own software can run on them. Smartphones, for example, are sealed systems where users have minimal control. The situation is somewhat better with laptops and desktop computers, although there have been efforts in the past to restrict access.

Spying and ads

Many believe software should be free, i.e., they don’t want to pay before (and often after) downloading a software. Business software like Microsoft Office is an exception — people will pay when it directly affects their income. But if you’re trying to get your app adopted by the public, it better be free. Or rather, appear to be free. Software is not free, of course! People just don’t mind giving away their attention and data for free.

They should mind though. Protecting your data goes beyond mere privacy. Looking forward, there is a subtle thread to free speech here. While we can speak freely today, the massive collection of personal data creates the infrastructure for future manipulation and control. Every piece of data collected builds a more detailed system for potential exploitation. The real danger isn’t just today’s targeted ads and manipulated content — it’s how this accumulated surveillance power could be used to restrict and shape public discourse in the future.

I also think the attenting thing is a big deal and tons of people are being manipulated into being willing, brain-off consumers.

Ads seem to be on the rise beyond free-to-download software. Even iOS comes with ads now, despite users paying $1500 for their iPhones. Similarly, you can pay a subscription for an improved experience using X (the experience will still be relatively bad I’m afraid), but some ads will stay (unless you pay for the highest tier).

The issue of online privacy has been known and discussed for years, but it feels like meaningful progress in protecting it has stalled. Everybody just kind of accepted it and went on with their lives as, in practice, everything seems to be going fine.

Slowness

The surprising thing about slow software is that people don’t seem to care or even notice. Whoever I describe the issue to, whether technical or not, shrugs at me. But it’s everywhere! A lot of the slowness can be found in stuff that runs in the browser, or is highly networked. Many local apps are also affected.

The main reason for slowness is that developers don’t care about their user’s time and, in many cases, economic pressure is not big enough to force them to make fast software. Users don’t notice how much slowness hurts them so they continue paying for slow software.

As a case in point, think of games. Games are fast because people choose snappy games over slow ones. Meanwhile, slowness proliferates in application software because users have trouble articulating what they dislike about the software they are using. They don’t recognize that constant delays fragment their focus, create persistent friction and a feeling of discomfort. Worse, the people making the buying decisions don’t see the economic damage that slow software inflicts on its users.

Much software is stagnant now because all the extra computing resources that became available over time are locked up in dealing with years of accumulated inefficiencies. There is no room for innovation if applications barely maintain usability despite running on powerful hardware. The path towards more powerful software making use of the abundant computing resources in existence today is blocked by this waste.

Slow software also makes people miserable as slow software fills each day with countless small and pointless annoyances that, however, are impossible to avoid. Users lack a mental model of what better software would look and feel like. They have accepted that clicking a button means waiting tenths of seconds for a response (this is the case with many interaction on LinkedIn for example), that typing in Word or Notion will always lack behind their keystrokes. In reality, these delays aren’t technical necessities — they are failures of design and implementation that we’ve been conditioned to accept.

Even cheap computers today are powerful enough to easily handle word-processing. But software developers have so thoroughly neglected performance that it seems you need to buy a $3000 MacBook to have an enjoyable experience writing some text. This wastefulness effectively excludes users who can’t afford high-end devices from an enjoyable computing experience.

Education

This is not a point about computer science programs. It’s about CS education for the public and non-computer scientists. Educating the public on computing is an important issue as, without digital literacy, users become susceptible to lies and manipulative practices of tech companies, accepting artificial limitations and poor performance as inevitable.

I grew up in Germany, a relatively wealthy country, but many high schools here don’t offer in-depth education on the basic use of computers or on advanced use and programming. The issue has been known for years, but not much is changing. I’m not sure iPads in classrooms are an improvement.

I’m at ETH now, a university famous for its computer science department. But the compulsory C++ class for physicists and mathematicians left many actively hostile towards programming. What troubles me most is classmates internalizing the failure: “I didn’t enjoy the class, but I know programming is important, and the issue probably is that I’m not one of those gifted programmer kids.” (I’m paraphrasing.)

The standard programming education seems to follow a common pattern: introduce a piece of syntax, assign tasks using that syntax, repeat with more complex features. The approach ignores a fundamental problem: students face rapidly escalating complexity before developing basic program comprehension skills. My classmates describe constantly feeling overwhelmed, forced to solve problems without understanding the underlying principles.

What can be done

By and large, the issues above aren’t new. Others have worked on these issues before to suggest solutions. What follows are my thoughts on improving the situation.

Control

I don’t have much to say here. Awareness needs to increase, so people choose products that they properly own and control. There must be (sensible) legislation limiting the anti-consumer practices of vendors. We also need to continue on the trend of building ever-improving (open-source) alternatives that respect the freedom of users and are serious competition to the products locking us in.

Spying and ads

Again, awareness will lead people to choose products that don’t spy on them, and viable alternatives need to be promoted or build. There is already now a web that’s pleasant to use although, like the quality operating systems, it’s mostly accessible to technical people (thank you, Hacker News, for being my portal to this world). Legislation may also be required, although I’m unhappy with past efforts here in Europe, as cookie banners are annoying and don’t seem to help much.

The advertisement industry (i.e., most social media and search companies) needs user data or else, they can’t sell ads effectively. There is no way around this. Instead of regulating the ability of advertisement companies to collect data on users, I’d rather look in the direction of finding new ways of financing these services. Kagi is building a search product, for example, that’s paid for with a subscription instead of attention.

Slowness

Software performance follows market incentives. If speed is a requirement for being commercially successful (e.g., games), then the software is often well-made and fast. In other domains, slowness is still seen as part of the nature of software and not much is done about it. It is clear, though, that people have a preference for snappy, responsive software. If there are multiple competing products that are effectively equivalent in all regards except for speed, the fastest one will win out. Casey Muratori gives an example highlighting the importance of speed:

Software will likely become more abundant with improving AI code-generation tools, as these make it cheaper to produce code. The code these tools generate may be inefficient, but, hopefully, they will force companies to prioritize performance as competition increases.

When it comes to action that can be taken now, I am still learning how to avoid the pitfalls that make even well-intentioned developers write slow software. I like the commentary of George Hotz, Casey Muratori, Rob Pike , and others on this issue. Some principles I find promising:

- Avoid dependencies. See if you can implement a feature yourself or import a small set of code into your project to do something. Depending on the domain, this is more or less doable. Even if you do need to use big libraries, be selective about them.

- Embrace simplicity. Clearly identify your goal and plan your solution to be simple. Complex problems have complex solutions, but many problems are simple in nature and can equally be solved in a simple way.

- Specific solutions are better than generic ones. Solve the problem immediately at hand and avoid the mistake of trying to anticipate use-cases that don’t exist yet. Predicting the future is hard, and focusing on what might be needed in the future will make it much harder to provide a good solution now.

I try to follow these principles, but of course I fail a lot myself and am still learning. My goal is to develop an understanding of software broad enough so I can be sure I’m not using a dependency because of a lack of knowledge of how to solve the problem myself. There are things that are better to delegate to an external library (encryption for example) but there should be nothing keeping me from sticking to a small set of high-quality dependencies.

Education

Attempts have been made to teach programming differently than by brute force. An approach used by Northeastern University was centered around slowly building intuition and the skills required to work on real-world code by using specially-designed teaching languages and providing systematic approaches to problem-solving. This is how they taught programming to CS majors over multiple courses. This takes time. The common argument that non-CS majors need only a quick programming overview misses the point. If schools consider programming important, they should invest the time to teach it properly.

Breaking away from conventional methods of teaching CS is hard, even assuming traditional approaches are deeply flawed. Prospective students are skeptical of unorthodox curriculums because it poses an extra risk to them if it turns out their non-standard education was sub-par with what other universities had to offer. I’m very interested, though, in how to teach non-CS majors programming, and I can see myself work on this in the far future. (Maybe I’m misled in wanting to fix this. It may just be that universities design introductory programming courses to be frustrating so they can filter for students that can manage the frustration.)

As for basic computer literacy, the path forward is clearer but requires sustained commitment. Years or even decades of ongoing investment would are needed. I’m sure it would pay off.

Hope

I am very passionate about software. Not passionate in the hollow, corporate LinkedIn resume sense, but in a way where poor software genuinely disturbs me and I spend tons of time obsessing over the state and potential future of software. My friends and family frequently have the pleasure of listening to me rant about issues discussed in this post. So it’s only appropriate I take the time and care to articulate them clearly in writing.

My hope is that growing public frustration with the current state of software will lead to meaningful change. I’m not going to become an activist anytime soon, but better software would be a good cause to fight for.